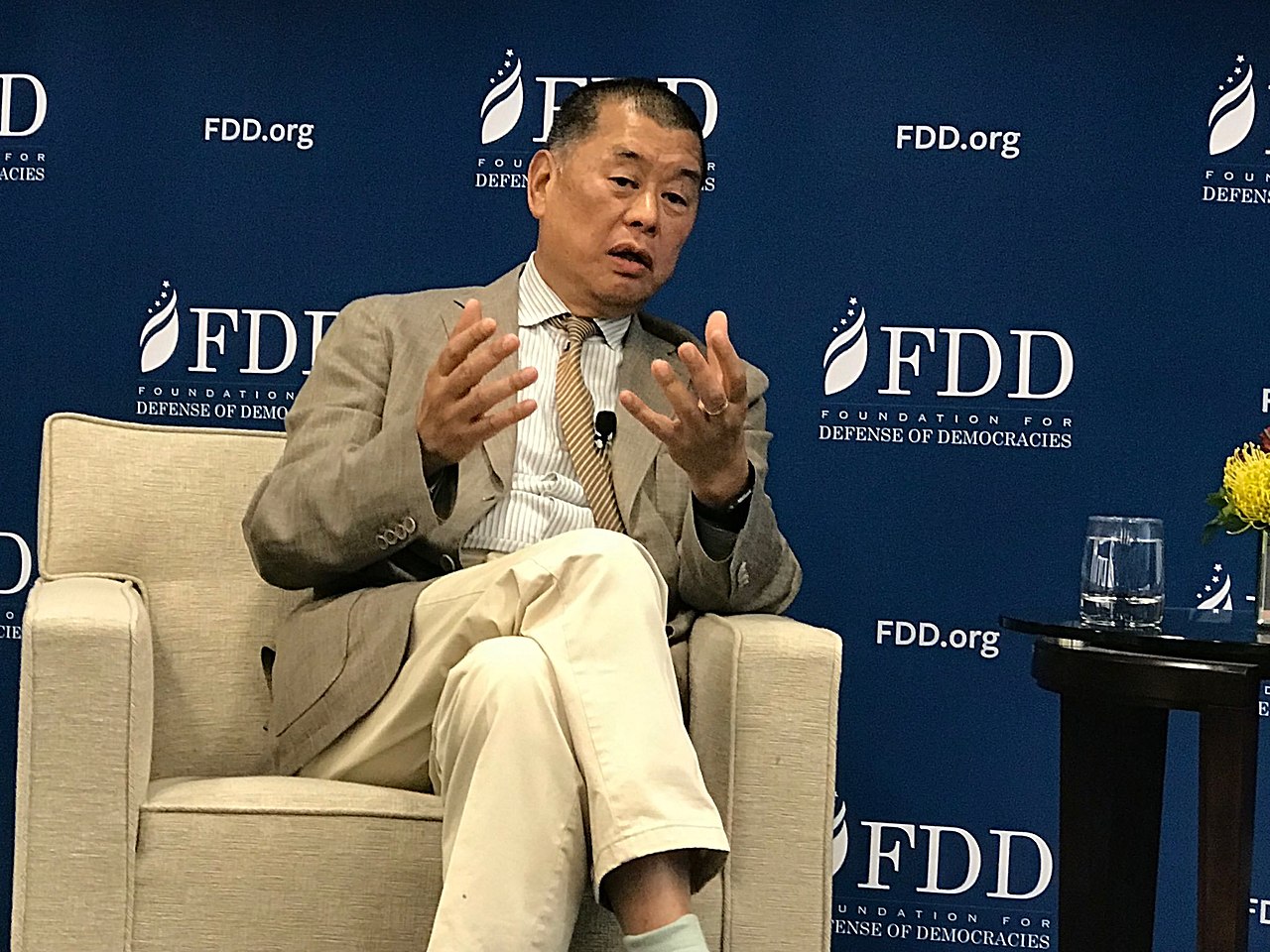

The story of Jimmy Lai, a 77-year-old Hong Kong businessman turned human rights activist and convert to Catholicism, is unfolding at the intersection of politics and religion between China, the Vatican, and the US. Of profound significance for those who cherish human dignity, freedom, and the enduring principles of Christian humanism, Lai’s activism led to his solitary confinement for five years. His commitment to his now-defunct pro-democracy newspaper, Apple Daily, led to his incarceration by the CCP. Lai’s persecution has come to represent the broader battle today for human rights, including freedom of, conscience in the face of 21st-century oppression.

In February, this battle took on an additional layer of complexity during Jimmy’s nearly 150-day-long sham national security law trial, with 47 days of testimony, when Judge Esther Toh, one of the presiding judges, made the striking remark, “We are Chinese,” directed toward him. This initiated a colloquy between Toh and Lai: Lai: “No, I am a Hong Konger because of One Country, Two Systems.” Toh: “Mr. Lai, are you yellow-skinned?” Lai: “If I am yellow-skinned, does that mean I am Chinese? I am a Hong Konger.” Toh: “You are Chinese.”

Toh’s remark, steeped in ethno-nationalist undertones, suggested that race dictates nationality, glaringly illustrating how there is no such thing as justice in Communist China. Toh’s unmoored legal reasoning dismisses out of hand Lai’s universalist aspirations for freedom and democracy as somehow foreign or un-Chinese, revealing a troubling alignment with Beijing’s narrative that pits ethnic identity against the principles of individual liberty Lai champions. Are the West’s claims to the primacy of individual liberty and democracy simply one more relativistic statement among many, perhaps true for Americans and Europeans but no one else? The CCP would certainly have us believe so.

Christian humanism, which emphasizes the universal dignity of all people, the moral imperative to safeguard freedoms and the pursuit of justice, is poignantly expressed in Lai’s plight. It echoes the Christian call to defend the oppressed, inspired by biblical teachings where the liberation of the captive is not just a political act but a spiritual obligation. From this perspective, Lai’s incarceration—and the judicial hostility exemplified by Judge Toh’s remarks—is more than a geopolitical issue; it’s a moral and ethical dilemma challenging the very essence of universal human freedom and dignity.

Enter then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, who in last year’s presidential campaign expressed a personal commitment to advocate for Lai’s release. In a candid conversation with Hugh Hewitt, Trump stated, “One hundred percent…I’ll get him out,” promising to leverage his relationship with Chinese President Xi Jinping to secure Jimmy’s freedom in the event he was re-elected.

It was also heartening to hear Vice President J.D. Vance pledge at the National Catholic Prayer Breakfast last Thursday: “The Trump Administration promises you, whether it’s here at home with our own citizens, or all over the world, we will be the biggest defenders of religious liberty and the rights of conscience, and I think those policies will fall to the benefit to Catholics in particular, all over the world.”

The promises of Trump and Vance evoke the intentional moral leadership of Ronald Reagan during the Cold War, who provided a lifeline to those behind the Iron Curtain in any number of ways, known and unknown. Known instances included when Reagan rallied by the side of former Polish Solidarity leader and later Polish President, Lech Walesa, and in his appeals for the release of jailed human rights activists in the Soviet Union, Andrei Sakharov and Natan Sharansky.

The scenario is now complex as the United States does not have the “Holy Alliance” with the Vatican as Reagan did with Pope John Paul II. This is further illuminated by recent developments in Sino-Vatican relations, as discussed in the Wall Street Journal article, “Chairman Xi Gets a Seat at the Pope’s Table.” Today, the Vatican is too conciliatory towards Beijing at the expense of human rights advocates like Lai. The Vatican’s approach, especially considering the controversial agreement on joint Vatican-CCP bishop appointments, is a return to the failed Cold War strategy of Ostpolitik, characterized by acquiescence, negotiation, and a total lack of criticism for Communist regimes. Now, the Vatican does not even tread a delicate line between resistance and compromise, as they did then. The Church’s approach to synodality—the practice of cooperation amid deep division—is way off the mark in a crucial aspect: standing in solidarity for justice and freedom, including those being persecuted for human rights advocacy.

The Church, as an institution that has historically stood for human rights and the sanctity of conscience, faces a pivotal moment. The Vatican, as under Pope John Paul II, must speak directly on these controversial issues, publicly appealing for the release of human rights activists like Lai, and others suffering under oppressive regimes. The time has come for Ostpolitik to end.

Lai’s story is a call to action for all who value human freedom and dignity. The Pope and the Vatican must advocate more robustly for human rights in their dealings with China by working with government leaders like Trump and Vance. It’s a plight that demands a reevaluation of how power, whether ecclesiastical or geopolitical, should be wielded in the modern world; not for control, but for liberation. Not for silencing the voices of the oppressed, but for amplifying them.