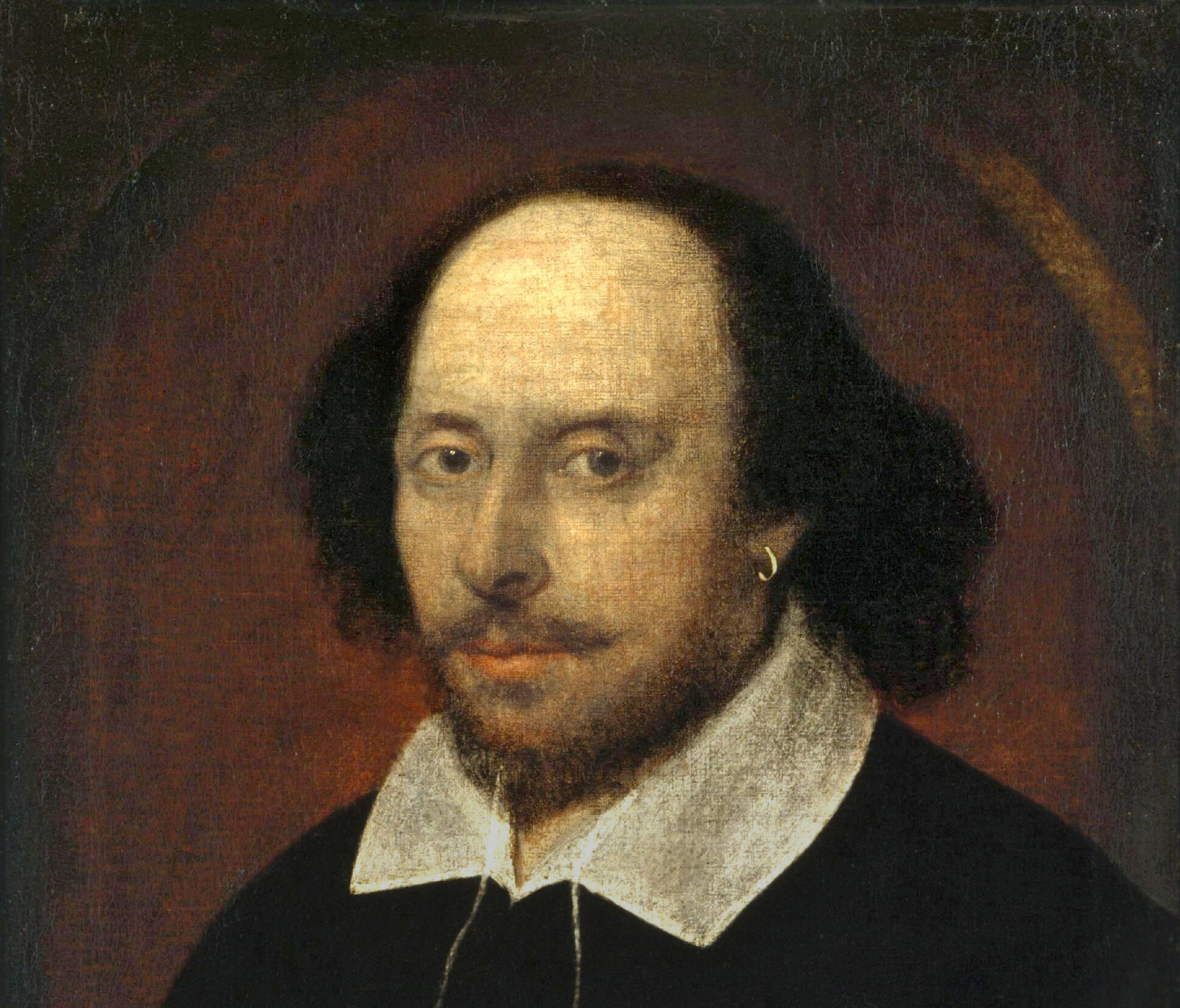

Not only is April 23 Saint George’s Day, the national feast of England, it is also the anniversary of both the birth and death of William Shakespeare, the finest poet that nation ever produced. But whereas today used to be a day to celebrate English heritage, and especially the Bard, ideological forces seek to turn the West away from this greatness. Just last month, for instance, the Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon announced that it would undertake to “decolonize” its collections because narratives about his genius “benefits the ideology of white European supremacy.” Student radicals on college campuses have taken up this argument as well, claiming that stripping Shakespeare’s works from syllabi and canons would somehow advance the cause of social justice.

Of course, these ideologues are not the first to protest against Shakespeare on moral grounds. A more sophisticated version of this attack was advanced by another giant of world literature, Leo Tolstoy, in a 1906 essay. The Russian author argued against conventional wisdom that Shakespeare possessed no sense of transcendent morality, asserting that his plays betrayed a fundamentally aristocratic attitude and lack of concern for the plight of the working classes. Tolstoy concluded that Shakespeare had no coherent philosophy; at best he was a cynic, and at worst a nihilist.

Ironically, perhaps, the aristocratic Shakespeare’s ablest defender was a democratic socialist – George Orwell. In a pair of essays from 1941 and 1947, the Englishman argued that the Russian misunderstood Shakespeare perhaps out of envy, but also out of a fundamental misconception of the purpose of art. He concedes that Shakespeare may not have been a systematic thinker, an entirely coherent thinker, or overly meticulous when it came to his plotting, but denied that this is enough to banish him from our libraries. The Bard created works of truly astounding beauty, and Orwell fiercely maintained this was worth preserving.

Orwell’s defense rests on the notion that Shakespeare does not, in fact, need defending. “There is no argument by which one can defend a poem,” he wrote, because “It defends itself by surviving, or it is indefensible.” A play has a different purpose than a treatise and does not require the same kind of tight, logical reasoning. Instead, the poet aims at moving the human heart – something Shakespeare clearly succeeded at for millions and millions over the centuries. “He can survive exposure of the fact that he is a confused thinker whose plays are full of improbabilities,” Orwell wrote. “He can no more be debunked by such methods than you can destroy a flower by preaching a sermon at it.” The continued reverence so many feel for Shakespeare’s plays is proof enough that Tolstoy’s attack failed.

While Orwell recognized that Tolstoy was not an “average vulgar puritan,” he also argued that his strident moralism was a somewhat surprising rejection of artfulness from one of the greatest writers to ever live. To some extent, this attitude could be attributed to Tolstoy’s conversion to a kind of ascetic anarchism in his last twenty years of life. According to Orwell, Tolstoy’s “main aim, in his later years, was to narrow the range of human consciousness” and detach himself and his followers from the physical world. As a result, he came to believe that “Literature must consist of parables, stripped of detail and almost independent of language.” For all the literary beauty he himself produced, Tolstoy ended up taking a position of extraordinary self-righteousness.

There is something, Orwell warned, “intolerant and inquisitorial in [this] outlook.” Ideological creeds serve as a pretext for bullying and the will-to-power. Their advocates come to despise anything that challenges their authority, and therefore seek to completely dominate politics and culture. Orwell was particularly clear-sighted about the way ideologues tyrannize the ordinary person’s “brain and dictate his thoughts for him in the minutest particulars.”

Needless to say, the ideologues of today are even worse. They have none of the respect for genuine art that Count Tolstoy had, and even more burning fury towards the past. A kind of cultural barbarism seems to be on the rise, and its votaries do not rest content with writing morally self-righteous pamphlets. In a dramatic fashion, some ideologues have even resorted to literal acts of terrorism against great works of art. But the efforts of the bureaucrats who run artistic and literary institutions to cut down Western civilization’s greatest thinkers are perhaps an even greater threat to our heritage.

Ultimately, Tolstoy’s failure to “debunk” Shakespeare – and the ideologues’ failure to “cancel” him – shows that poets are not simply political writers or propagandists. Their art concerns a wider view of human life. As Orwell put it, “If one has once read Shakespeare with attention, it is not easy to go a day without quoting him, because there are not many subjects of major importance that he does not discuss or at least mention somewhere or other, in his unsystematic but illuminating way.” Shakespeare’s plays speak to every aspect of the human experience – and none more profoundly than King Lear – the play to which Tolstoy most strenuously objected.

It is, by all accounts, a strange play. Through a jumble of pagan and Christian symbols, Shakespeare tells the story of an aging sovereign who steps away from the responsibilities of the crown, only to watch and suffer as disaster ensues. His hubris costs him not only his power, but also the things he loves the most. It is perhaps the most painful of Shakespeare’s tragedies, and among the most difficult to interpret. Tolstoy particularly despised it for its seeming lack of harmony, but in the aforementioned essays Orwell ably demonstrated its artistic merit. And yet one particular aspect of the King Lear demonstrates the profound philosophic importance of Shakespeare’s poetry.

At almost the exact center of the play, Lear experiences a moment of piercing ethical clarity that reflects the heart of the Shakespearean moral imagination. Wandering through a raging tempest on the blasted heath, he and his friends eventually find a hovel in which to take shelter. But rather than entering first, Lear tells his friends to go in before him while he prays in the storm. In a brief speech, he reflects on the sorry circumstances of his subjects caught in the squall:

“Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness defend

you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, pomp.

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou may’st shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.”

To put it less poetically, Lear’s own experience of terrible tragedy has increased his capacity to understand and empathize with the suffering of others. His descent from the heights of kingship to the edge of madness taught him something universal about human nature, something that enables him to understand his subjects a little bit better. If ideologues seek to, in Orwell’s phrase, “narrow the range of human consciousness” to their small doctrines, by contrast Shakespeare’s poetic faith is that the stage and the written word can instead expand it.

As the Digital Revolution continues apace and we find ourselves increasingly locked within online echo chambers, we desperately need that poetic faith to restore a common culture. The ideologues denigrating Shakespeare are not making the world a compassionate place, only a smaller one. The good news, though, is that their efforts cannot succeed in the end. “So far from [Shakespeare] being forgotten as the result of Tolstoy’s attack,” Orwell wrote, “it is the attack itself that has been almost forgotten.” The same will be said of today’s cultural barbarism. For all its moral stridency, ideology will eventually fade away. But Shakespeare, like all great art, will endure.